Shop 'Til We All Drop

The basic point of Prestowitz' piece is that the world's globalized economy has evolved a functional but unstable status quo. In essence, the rest of the world--but particularly Asia--produces things, and we in America consume, consume, and consume some more. Consumption of the stuff that that other people produce has now become America's vital, and in some sense only, role in the world economy.

For years now Americans have held to the belief that while we may import cheap manufactured products from abroad rather than producing them ourselves, we balance that out with the world's best high-tech and technical service industry, along with a thriving agriculture sector (though not thriving for the American small farmer, but that's a subject for another time). Unfortunately, this belief no longer holds true: In under ten years we've gone from a high-tech trade surplus of $30 billion to a deficit of $40 billion. Well-educated and highly skilled workforces in China and India can now compete with the American worker on a level playing field thanks to the internet and complex transportation networks, and the fact that they require lower costs means that the decision to produce your semiconductors in New Delhi rather than Cleveland is a no-brainer. And as if that weren't already cause for concern, now a trade deficit even exists for American agricultural products for the first time in history. America's modern economy has become a giant black hole of consumption from which almost nothing of tangible value escapes.

So how, then, are we able to maintain our extravagant lifestyles despite the fact that we produce less and less of value every day? It's a simple strategy that both the country as a whole and we as individual Americans have adopted wholeheartedly: We charge it.

As Prestowitz puts it,

"For the United States, globalization has meant building its economy into a giant consumption machine. Easy consumer credit, home-equity loans with tax-deductible interest payments, markets largely open to imports, policies that emphasize growth through demand management and accommodative monetary policy, and myriad other incentives have led Americans to save nothing while both households and government borrow at record rates. This is often justly criticized as excessive. But it is important to understand that American buying drives most of the world's growth because the United States is virtually the only net consuming country in the world."

But isn't this a win-win situation? Americans borrow money like there's no tomorrow to finance lifestyles that we couldn't otherwise afford, and the world's other countries support their own economies by selling us the stuff we want. Why doesn't everyone just shut up and be happy?

Well, aside from moral issues and the spiritual vacuousness created by living in a society that exists only to consume, this system can't last forever. Oh, it functions alright for now, because the rest of the world will keep allowing us to borrow and keeps investing in the U.S. dollar. The way the system is currently set up, they NEED us to continue to buy what they produce. We are essentially the only country on earth that fulfills a very key role, namely buying much, much more than we produce. If tomorrow we wake up and stop consuming, the world economy would be in shambles. So because the rest of the world is as invested in this lopsided system as we are, things may seem to run smoothly for a time. But the party can't go on forever.

"The growing trade imbalance . . . makes the current mode of globalization unsustainable. To finance the deficit, the United States is already absorbing about 80 percent of available world savings. The value of U.S. imports is now more than double that of exports. To merely stabilize the deficit at its current rate would require that exports grow more than twice as fast as imports.

But this cannot happen if the supply side continues to move offshore. If it doesn't happen and the deficit keeps growing, world savings will eventually be insufficient and a financial crash will be inevitable."

In other words, in the end there just isn't enough money in the world to support this system as it currently exists. It won't be today, it won't be next month, but sooner or later this imbalanced system will either collapse or evolve into something else.

So what's the answer? How do we avoid calamity? Well, I think it would be a positive start for those of us living in this great consumer culture to admit that a society in which we produce so very little and buy so much is fundamentally unsound. Then we're going to have to do something that we as Americans have never been very good at; we're going to have to show some restraint. At the very least, we should consider whether borrowing money to support opulent lifestyles is really such a good idea. Our standard of living may be the envy of the world (at least among the more well-to-do segments of our society), but it isn't worthwhile if we mortgage our nation's future economic wellbeing to achieve it. And while we're at it, we're going to have to find ways to create markets overseas in order to soften the impact on the global economy of a reduced rate of U.S. consumption. And if possible, is it asking too much that we find ways to start MAKING things in America again? We used to be so good at that.

Like it or not, a global economy is what we have and we must contend with that reality. But just as over-consumption and excessive debt are no way to run a household, it's also no way to run the nation's economy. Just some food for thought this Christmas season.

Dinner included Turkey steaks (I didn't think we needed a whole breast), mashed potatoes and gravy, stuffing, crescent rolls, and a chicken and green bean casserole that Melissa made. Everything came out really well if I do say so myself. I felt like a picture was necessary since this is probably more cooking than I will ever do again in my life.

Dinner included Turkey steaks (I didn't think we needed a whole breast), mashed potatoes and gravy, stuffing, crescent rolls, and a chicken and green bean casserole that Melissa made. Everything came out really well if I do say so myself. I felt like a picture was necessary since this is probably more cooking than I will ever do again in my life.

and the National Bowling Stadium.

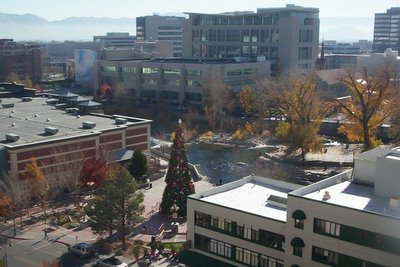

and the National Bowling Stadium. Well yesterday the City of Reno officially opened up the redesigned and remodeled

Well yesterday the City of Reno officially opened up the redesigned and remodeled  The ice rink is right in the heart of downtown in a public park on the Truckee River. It's great to have the rink back, but what's really nice is to see that the redesign of the plaza that hold the rink includes these interesting two-foot high, solid stone architectural features:

The ice rink is right in the heart of downtown in a public park on the Truckee River. It's great to have the rink back, but what's really nice is to see that the redesign of the plaza that hold the rink includes these interesting two-foot high, solid stone architectural features:

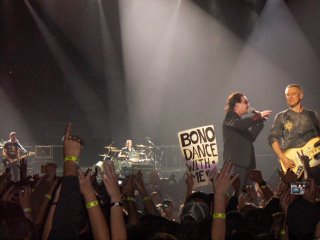

My sister Maureen went to see U2 in Atlanta last week. She sent me this picture, which she got off of a cameraphone. This is actually the second time she's seen the band, the other time being sometime around the late 80's or early 90's (which I think would have made her about three or four years old at the time ;-)). She says that back then everyone held up cigarette lighters, and now everyone holds up cameraphones.

My sister Maureen went to see U2 in Atlanta last week. She sent me this picture, which she got off of a cameraphone. This is actually the second time she's seen the band, the other time being sometime around the late 80's or early 90's (which I think would have made her about three or four years old at the time ;-)). She says that back then everyone held up cigarette lighters, and now everyone holds up cameraphones. This is a shot of the tree from it's base a moment after being lit. I would like to have gotten a picture that gives you a sense of the size of the crowd which showed up to watch the lighting (it probably helped the attendance numbers that lighting ceremony was also the end destination of the

This is a shot of the tree from it's base a moment after being lit. I would like to have gotten a picture that gives you a sense of the size of the crowd which showed up to watch the lighting (it probably helped the attendance numbers that lighting ceremony was also the end destination of the  I'm not exactly sure who these folks were. They were some kind of chorus dressed in Renaissance Faire clothing, except for the guy in back who obviously thought it would be just sooo wacky to wear that candy cane hat. They sang Christmas Carols before the lighting of the tree. Actually the one who stole the show was the woman in the front row on the left, who was very animated and sort of acted out every verse of the song.

I'm not exactly sure who these folks were. They were some kind of chorus dressed in Renaissance Faire clothing, except for the guy in back who obviously thought it would be just sooo wacky to wear that candy cane hat. They sang Christmas Carols before the lighting of the tree. Actually the one who stole the show was the woman in the front row on the left, who was very animated and sort of acted out every verse of the song.

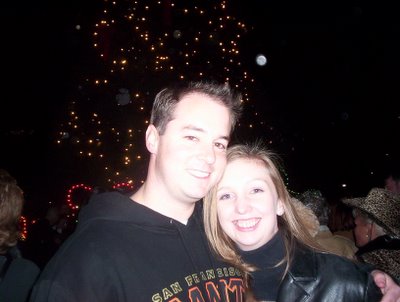

Dominique was nice enough to turn the camera on Melissa and I and snap this picture. It is not her fault as a photographer that I appear so pasty--that's just my genes.

Dominique was nice enough to turn the camera on Melissa and I and snap this picture. It is not her fault as a photographer that I appear so pasty--that's just my genes.

Never to be outdone, of course, is my other niece Kira.

Never to be outdone, of course, is my other niece Kira.

The developers who are planning to convert this behemoth into condos will be

The developers who are planning to convert this behemoth into condos will be